Kathryn Schneider Smith

Wisconsin Magazine of History

Summer 1996

STEPPING into the Society’s Office of Public Information as assistant supervisor in June, 1961,1 felt a rush of possibilities. To be moving from being a student user of the grand, hushed, marble-clad library to taking some actual responsibility in this august place seemed the greatest good fortune. As it turns out, it was.

I was warmly received as a colleague. Although, with the overconfidence of untested youth, I considered myself equal to any challenge, I now wonder at the trust placed in me to write, edit, and design Wisconsin Then and Now, manage two school magazines, travel the state to publicize historic sites, run a statewide photo competition for the Wisconsin Calendar, plan public relations events, and generally try my wings. The sense of family that pervaded the place was reinforced by the camaraderie of Friday-after-work gatherings at Troia’s Steak House, lunches at the Union, and after-hours gossip sessions at the annual meetings. I remember often being scared by my responsibility. (Why didn’t my boss Chet Schmiedeke, or Society director Leslie Fishel, look over my shoulder more? Why didn’t they tell me what to do?) I have since advised other beginners lucky enough to be in similar situations that it is a gift. Take it and try everything.

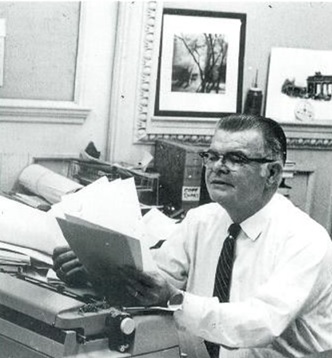

The Society was trying everything too. The Mass Communications History Center, led by Barbara Kaiser, was developing a new mission with major accessions. The new Office of Local History had begun to connect and assist small historical societies around the state. Joan Freeman, the Society’s curator of anthropology, was uncovering dramatic traces of prehistoric Aztalan near Lake Mills. Stonefield Village, the Society’s first experiment with an outdoor museum, was being assembled at Cassville. Museum registrarjoan Severa was building the Society’s costume collection and bringing it to the public with fashion shows in local department stores. The Society supplied a home for the nascent American Association for State and Local History, which under Clem Silvestro operated out of one small room next door to the Public Information Office. School Services director Doris Piatt was experimenting with history education on television, dragooning staff members such as myself into terrifying stints before live cameras, wearing, and using, odd objects from the collections. Underlying it all was a dedication to involving the public in the enterprise of saving and using the past, a commitment I took for granted—having been thoroughly imbued with the “Wisconsin Idea” that “the boundaries of the university are the boundaries of the state.” The Society was not only teaching but was also encouraging and publishing scholarship, a dynamic combination I assumed was typical of historical societies. Setting the standard was Research Division director Alice Smith, who was just beginning Volume I of the Society’s new multivolume history of the state. My closest experience with dedication to scholarship, however, came from working with Bill Haygood, who presided over the Wisconsin Magazine of History with devotion, humor, and soul. He became my supervisor when, after several years, the Society’s two school magazines were added to my responsibilities and I moved to the Publications Office. I remember Bill, his eyebrows raised in disbelief, periodically emerging from his office to read some mangled prose sent his way (“and lone behold”), or to recite an overheard malapropism (“so sick, he was rushed off to the hospital in a avalanche”). Charlie Glaab, a scholar in residence, would stop by to pass the time (“I could say my name is pronounced Glabe, but it’s Glob”); only later did I recognize the pioneering nature of his research in the new field of urban history. And just down the hall were the seemingly bottomless resources of the Society’s library, manuscripts division, and state archives, being augmented by an aggressive field services office—all available for my reference, all a source of ideas for Then and Now.

William C Haygood working on an issue of the Wisconsin Magazine of History

in the late 1960’s.

Paul Vanderbilt, curator of library’s Iconographic Collections, opened my eyes to images as sources of information as well as illustrations, long before such thinking was acceptable. I remember sitting in his tiny, cluttered, dimly lit office on the fourth floor, interviewing him for a story for Then and Now on a new exhibit. He shared his passion for pictures that revealed the spirit of a person, place, or time in an unexpected gesture, in a detail in the background, or in the quality of light. I remember him saying that pictures should be organized around such titles as “parades” or “Sunday afternoon,” instead of traditional dates and places. Only later did I realize that Paul had organized the incomparable Farm Sectxrity Administration photograph collection at the Library of Congress, which I often now use, with this philosophy as a guide. The opportunity to spend time, sometimes alone, in the historic rooms of the Society’s scattered historic sites and hotxse museums provided a similar lesson in the power of objects, room arrangements, and landscapes to bring the past into the present. The view of the Mississippi River from first governor Nelson Dewey’s living room at Stonefield in the silence of a gray afternoon is with me still. Often my trips to do site publicity work were solitary, taken in my two-tone 1955 Pontiac sedan through small towns where I would seek out the local hangout for lunch: meat loaf, mashed potatoes and gravy, and homemade pie. I still love finding the heartbeat of a little place in a local eatery, a legacy of those trips. Apparently my car amused some of my colleagues. The year the Ford Mustang appeared on the market, I won a two-week free use of a convertible at a Madison Press Club event. Some older members of the staff took fatherly roles in advising me whether or not to buy the car. Conservative views prevailed, and I did not. Years later, the Society’s business manager, John Jacques, told me that he had made one mistake at the Society: “I should have told you to buy that car.” My monthly cranking out of stories about Wisconsin past and present, my travels around the state, my shuffling through hundreds of photographs for the calendar with Mary McCann gave me more than a professional base.

It also gave me an understanding of what it meant to be from Wisconsin. It taught me the importance of a sense of place; of having, as Martin Marty has put it, a place to stand to view the world. And so when, in summer of 1965, I moved to Washington, D.C, to do press work for Senator Gaylord Nelson, I looked for that sense of place in my new home. I looked around me for the places where its spirit and history were kept. The Smithsonian is a storehouse of national treasures. But the city of Washington? There was no local museum devoted to its understanding, no local history curriculum in the public schools, and seldom any local history features in the ewspapers. I called at the local historical society, then known as the Columbia Historical Society, in the early 1970’s, to see what went on there. Informed that it was open froiu 2 to 4 on Saturdays, I appeared at the appointed hour to find the door opened only a crack upon my ringing. A clearly apprehensive older woman inquired what I wanted. “To come in,” I replied. “The librarian isn’t in today,” she replied. “I don’t want to use the library,” I said. “I want to see the historical society.” Itwas, I realize now, an unusual request of a society of an altogether different tradition—an organization of individuals for whom the preservation of history was a highly motivated but largely private enterprise. When I inquired about how I could join and was asked, “Who do you know?” I was rendered by my midwestern SHSW experience unable at first even to grasp the meaning of the question. I suddenly recognized, and have come ever more clearly to understand, what a remarkable institution I had been part of in Wisconsin. My career in Washington has evolved, but thirty years later the spirits of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin still whisper in my ear and guide my course. Building a sense of place in a city with little self-identity as a hometown seems to be behind it all. My husband and I have sought out and reveled in real communities in which to live and work—Capitol Hill, Dupont Circle, and Cleveland Park; for some time Sam edited and published, and I assisted with, a neighborhood newspaper. After adding a master’s degree in American Studies to my journalism credentials, I edited a book on Washington neighborhoods and published a study of neighborhood change in Georgetown.

Today, working as an independent public historian, I am, among other projects, helping to create a community-based history center in a neighborhood that was for decades the heart of the African-American community in Washington. What can be traced most directly to my experience at the State Historical Society, however, is my work with D.C. public schools in creating a now-required ninth grade D.C. history curriculum—inspired by SHSW school services—and my efforts, as board president, to imbue the old Columbia Historical Society with some of that sense of public mission I had absorbed in Wisconsin. Today, the organization is called The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Its board is male and female, black, white, Jewish, Hispanic, and Asian; its programs and membership are reaching into the community; its unanimously endorsed mission is public education.

The Records of the Columbia Historical Society have been transformed into a semiannual scholarly journal, Washington History, which I created and edited during its first three and a half years. It is a child of the Wisconsin Magazine of History and Wisconsin Then and Now. It is designed to reach both scholar and layman. Its use of photographs breathes Paul Vanderbilt; its scholarship breathes Bill Haygood. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C, has a ways to go to be the organization its city deserves and to be financially secure in a place where, unlike Wisconsin, there are no public monies for local history. But it is on its way. And it should be recorded in the archives of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin that there is a flame burning in the nation’s capital that was lit at 816 State Street in Madison.